Spirit of Soccer’s mission is to use the power of football to educate children about landmines and explosives through its multi-award winning Mine Risk Education (MRE) programme. In Iraq, since 2009 Spirit of Soccer have delivered programs in Baghdad, Basra and Kirkuk to over 80,000 children, often under heavy shelling. This has included training 18 local Iraqi coaches, including three women, from across the Arab, Sunni, Shia, Kurdish and Christian communities.

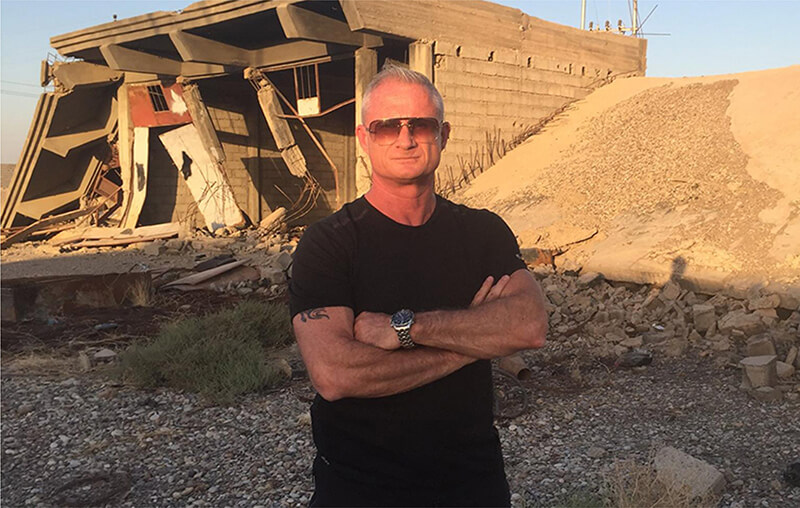

We spoke to Scotty Lee, Founder of Spirit of Soccer, about the threat to football from the current conflict in Iraq, clearing landmines in conflict zones and being nicknamed the “Soccer Special Forces” by the military. Scotty started Spirit of Soccer in 1996 after witnessing a group of children in Bosnia set off a landmine while playing football – three of the children were killed, four were maimed. All were under ten years old.

How is the rise of Islamic State in Iraq affecting Spirit of Soccer?

There are certain areas we cannot operate in any longer. Three of our coaches have been made refugees in their own country, and we have one coach who is trapped in an Islamic State controlled village, and he cannot get out.

Is the tide turning?

Daesh (Islamic State) is a very well organized, well-funded organization and are very sophisticated in the way that they distribute money. They produce and perform a lot of social services from garbage collection to law enforcement, albeit in a very brutal way. The tide will turn against such brutality but it will have to be led by the Islamic world.

The tide will turn, but not just with bombs and guns. A lot of these lads, they are religious people, they have seen the West take liberties and they are angry. When you are an angry young man – you can go round streets in Tottenham or Hackney in London and find the same sort of people – you just want to belong to and feel part of something. If we can use sport as a force of good and work with Muslim scholars to create a curriculum where the pillars of Islam are relevant to the pillars of sport – fair play, respect, charity and helping each other – we can create an opposite force to this evil.

How big a danger are land mines in Kurdistan and Iraq?

Our job is to keep children alive until all these weapons are pulled out of the ground. It might take another thousand years, it may never happen. There are mines on the Iraqi-Iranian border, up in the mountains. They will stay there. They will kill two or three shepherds a year. They know they are there. If they are going to take the risk, fine. But in Basra the biggest problem we have is that there has not been any regular garbage collection service since the invasion in 2003. So the locals burn the garbage. It is usually the job of the young boys to burn the garbage. Where they burn it there are often huge artillery shells from the British or the Americas or from the Iraqis, Al-Qaida, Daesh, it doesn’t really matter which group they belonged to. Then bang…

How does the Spirit of Soccer programme work?

For a Spirit of Soccer training session we set up a series of skill stations. The skill stations could be themed around communication, teamwork or recognition. They are soccer drills, but subliminally they are related to the Mine Risk Education messages that we promote. We might talk about recognition – recognising a moment in a football game. But then we will talk about recognising what weapons look like, or what a mine site looks like, both conventional and unconventional. At the end of the training session we do a 10-minute summary of how do you survive these weapons. The session is 90 minutes in total, because you do not want the children getting bored.

When we first came up with the philosophy of Spirit of Soccer 20 years ago, my heroes were Kevin Keegan, Pele, George Best, Glen Hoddle, but also my local PE teacher, who was a good footballer and the captain of the local football team. So we aim to create local role models within the community, who can then go out and engage kids with good quality coaching. We make sure they get proper qualifications. We often work with the national football federations, so our coaches walk away with a national or internationally recognised coaching qualification, which helps them with employment later on.

Spirit of Soccer also runs festivals for larger amounts of people and coaching workshops, teaching these skills to people who work for other NGOs, who can then go and implement this training in their community. In Laos we recently did this for 37 women, who all work for NGOs in their community. So there is the ongoing Spirit of Soccer patented curriculum and then there are other festivals and coaching workshops.

Why is Spirit of Soccer so important and effective?

If you can show a kid how to drop a shoulder or do a Ronaldo turn, hopefully he will trust you enough to say “ok, this person has told me how to play football and improve my skills, maybe I should listen to him when he starts talking about these weapons”. There is a very leading question of “Who wants to be the next Ronaldo, the next Beckham, the next Messi, the next Rooney?” Well you can’t do that if you have only got one leg, no eyes, or no face. If you want to be a professional footballer you need to be fit and healthy, you need to take care of yourself; you need to take care of each other.

We keep our education session to 10 minutes for the children because anything longer than that, their minds are going to wander. It’s mainly question and answer, because we really need to know what they know about these weapons. From that local intelligence, occasionally we will discover locations of minefields that no one knows about. In Cambodia recently we were talking to the kids, who told us there had been an explosion and a cow was killed. We spoke to a teacher and he remembered fragmentation mines being laid there 25 years ago. Spirit of Soccer has the power and authority to call an emergency team and they cleared 16 fragmentation mines that were just 5 metres from the classroom. The mines had been in the bushes for 25 years and no one knew anything about them. So we make a difference in getting information to have weapons cleared, especially when they are near schools and homes.

We are specialists in what we do with weapons. But we do so much more, especially with the amount of education we supply and the gender equality we create with our women coaches. There is an incredible amount of women playing football in Cambodia because of Spirit of Soccer. We started women’s football in Cambodia, Laos and a lot of these countries.

How do you decide where to hold a Spirit of Soccer training camp?

Spirit of Soccer works especially in Cambodia and Iraq by getting reports of mine injuries. At the end of every month we can find out where these injuries occurred, how many people were killed or maimed, the type of weapon that caused these injuries and what was the activity. We can then target those areas through the Ministry of Education. For instance we might go to Hanakin due to a spike in child casualties there, and we receive a list of all the schools and clubs reporting to the National Government. They give us permission to set up a schedule with the coaches, and we go out and start working in those schools and clubs. We are quite fast in reacting to where the problems have arisen and the injuries that are occurring. There is no point doing work where no one is being killed. We are where the problems are.

How important is it to identify and work closely with existing local organisations?

Lots of the children we coach already play for teams or clubs. In Cambodia and Laos, we work with the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport. In Lebanon we work with the Islamic Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts. We might work with a club, a village, or any local organisation. Most of my coaches are PE teachers in the community. Generally our three natural implementing partners are the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport, the national football federation and the National Mine Action Centre.

Our sessions become a bit of an ‘event’ for the local area. Particularly when we run tournaments, we get a lot of interest from the tribes. A lot of tribal elders come, you get a lot of political support, and the security forces turn up. They all like football. It is a good way of garnishing local support and local security for my teams, because they do not have bodyguards. Once they meet at a football tournament the security forces are more likely to look out for them when the football is not going on.

Where were these photos taken and are the children here mainly Kurdish or Arab?

Most of these photos were taken just outside Kirkuk in the Kurdish region of northern Iraq. The city of Kirkuk itself is split into two, the Kurdish region and the Arab region. On occasions villages are a mixture. But can you tell if these kids are Kurdish or Arab? I can’t tell…

Some of the photos were near Halabja, up on the border where Saddam gassed the Kurds. One coach is a PE teacher who has been working for Spirit of Soccer for about 6 years now and he just got married.

How much of your focus is on working with girls in Iraq?

About 25% of our target audience in Iraq is girls. In northern Iraq it is a lot easier. In central Iraq we work closely with local imams and have to be careful. In Hanakin we have two female coaches and they work just with the girls in very conservative areas. In Basra itself it is not too bad, but outside Basra by the Kuwaiti border we have to be careful how we approach and involve the girls. Everything is done on a cultural basis and a local basis with the local imams. A lot of women love to play football and getting them playing together at an early age is something quite profound. You get some powerful images when you have our female coaches in hijab training young men.

Who built these incredible football pitches?

The Kurdish government (KRG) and then the Iraqi government with a lot of Turkish money and Norwegian money started constructing these pitches. The Kurds originally got around $28m to build the plastic pitches. They are now found throughout northern Iraqand also now in central Iraq. The trouble is that they are locked up a lot of the time and it is hard to access them, with the keys belonging to a certain person. We have very close relationships with the authorities, the security services, with everybody. So we can use them whenever we like. They are used a lot, but to be honest these pitches should be open for the kids 24 hours a day.

How do the military view you?

Within the military Spirit of Soccer has been called “Soccer Special Forces”. We’ve been shelled with rockets while coaching. But the most important thing is to tell the story of these amazing children, their families and our coaches, who wake up every morning and go to work. They are doing it day in, day out. They are heroes.